The oldest of all the modern ballroom dances, the Viennese Waltz is a fast moving dance expressed most beautifully when a large group of dancers is on the floor at the same time. Which makes sense when you understand how it began. Here’s a look at the history of the Viennese Waltz.

Danced in fast 6/8 time, its main characteristic is continuous rotation to left and right throughout the dance. In many parts of Europe, a reference to the “Waltz” is automatically assumed to mean the Viennese Waltz. When you mean the slow modern version, you have to expressly refer to the “Slow Waltz” or “Modern Waltz.” But the dance actually shares few characteristics with its slower cousin.

The Viennese Waltz originates from the Volta, a couples-focused dance enjoyed by high society in the 1500’s.

The Viennese waltz emerged in the second half of the 18th century from a German dance called the Volta (or Lavolta) and later the Ländler in Austria. The Volta was danced by members of affluent society and became scandalous because of its closeness and technique, causing it to eventually fade from existence. But the high society connection developed a focus on posture and elegance that remain key characteristics today, along with the rotational emphasis of the figures.

The Ländler, in contrast, was danced by farmers and common people, even while sharing the same music and many of the same technical characteristics. The Viennese Waltz gained ground through the Congress of Vienna at the beginning of the 19th century and by the famous compositions by Josef Lanner, Johann Strauss I and his son, Johann Strauss II.

The Volta ushers in a new approach to dance

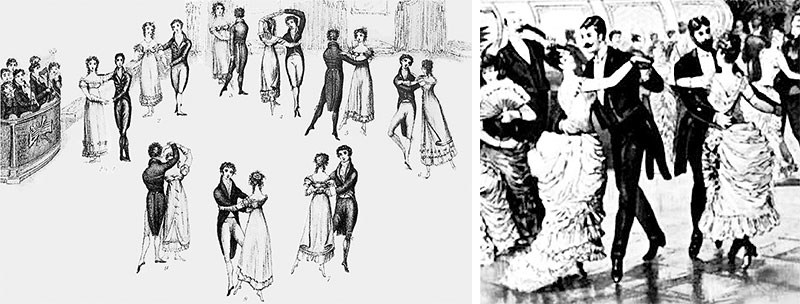

Popular between 1550–1650, the Volta was not only the most athletic and controversial of a series of dances known as the Galliards, but also the only court dance of the period performed by a couple in a closed embrace. It ushered in a whole new way of looking at dance.

Until the Volta, men and women did not dance as couples. Dances had always been sequence dances, in the style of line dancing, where couples would dance the same steps side by side in groups. With the Volta and the Ländler, that all changed. These dances featured men and women dancing mostly as individual couples.

While the figures would sometimes be danced side by side or in shadow position, the rotational sequences required the couple to face toward each other. Because of the speed of the rotation, couples soon realized that the closer the partners were to each other, the more efficiently they could turn as a couple.

When dancing the Volta, partners held each other tightly and matched steps to heighten the centrifugal force as they twirled around in a series of ¾ turns. The dance’s signature move was a leap in which the man lifted the woman into the air and spun her around before setting her down again. The footwork of the Volta actually consisted of only five steps, with one count held as the man lifted the woman into the air in the leaping move called a Caper.

The Caper required precise execution. The man held his partner tightly around her waist, and lifted her into the leap by placing one hand on her back and his other near her crotch, on the bottom of her busk. Pivoting on one foot, the man lifted his other knee under the lady’s buttocks and propelled her into the air. The woman used her right hand to press down on her partner’s shoulder and her left to hold down her skirt to avoid revealing her chemise or bare thigh.

The dance drew the attention of those who believed such close public contact between men and women was leading society to destruction. As early as 1592, Johan von Münster described his horror at seeing men grasp the lady in “an unseemly place” and called for the dance to be banned.

In Vienna, the city that later became known as the center of the waltz craze, an ordinance was passed in 1572 which warned, “Ladies and maidens are to compose themselves with chastity and modesty and the male persons are to refrain from whirling and other such frivolities.”

It is said that Louis XIII (1610–1613), heir to the French throne, considered the dance indelicate and therefore forbade its use at court, bringing about the Volta’s eventual demise. But Queen Elizabeth loved the Volta and especially the Caper, causing the dance to remain popular in England long after it began to fade in Europe.

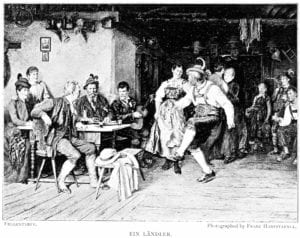

Enter the Ländler

The Ländler was one of several alpine, turning folk dances popular in Germany, Bavaria, Austria and Bohemia. These couple dances, all performed in a close embrace while rotating, were grouped together under the generic name of Deutsche (deutsche Tänze) or “German dances.”

It’s not clear when the term Waltz entered the picture, but the turning figures in these dances were referred to as “waltzing” sometime during the 1600’s. The Ländler had many of the same characteristics of the Volta, but was originally danced by ordinary working-class people as compared to the elite. As the Volta faded, the Ländler began to grow in popularity. But it too drew controversy.

Attempts were made to ban the Ländler. Stern warnings were issued from church pulpits against doing any “German waltzing dances” in the streets, and the bishops of Wurzburg and Fulda issued decrees prohibiting gliding and waltzing.

A 1797 pamphlet against the dance was entitled “Proof that Waltzing is the Main Source of Weakness of the Body and Mind of our Generation”. But even when faced with all this negativity, it became very popular in Vienna and once again enjoyed the participation of all levels of society.

Popularity grows against opposition

Large dance halls like the Zum Sperl in 1807 and the Apollo in 1808 were opened to provide space for thousands of dancers. The dance reached and spread to England sometime before 1812. It was introduced as the German Waltz and became a huge hit.

The massive Apollo Hall became the center of the waltz craze in Vienna from 1808–1812. The Apollo had five large ballrooms and forty-four other public rooms, in addition to three glass houses, thirteen kitchens, an artificial waterfall, a lake with live swans, and flowers and trees that bloomed year round. Everything in the Apollo was done on a grand scale. One chandelier in the dining room held 5,000 candles. The musicians were tastefully hidden so that as the elite of Vienna swirled around the floor, the melodic strains of the waltz seemed to float down from the sky itself. Opened on January 10, 1808 to celebrate the engagement of the Emperor Francis I to his third wife, Princess Maria Ludovica d’Este, the Apollo Palace could accommodate up to 5,000 patrons. The entrance fee for the inaugural soirée was 25 guilders, an exorbitant sum in those days. The dancing hall catered to the wealthiest citizens of Vienna, and stories were shared of members lighting cigars with burning bank notes.

The Tivoli Pleasure Gardens, which opened in September of 1830, was another popular spot for waltzing. The gardens contained a spectacular colonnaded dancing pavilion that overlooked all of Vienna. One of the added attractions at the Tivoli was a toboggan-like chute with four tracks that allowed sixteen carriage-type cars mounted on sledges to speed excited patrons up and down.

Learn more about Viennese Waltz technique

It was in these elegant dance halls that Johann Strauss I became famous for his Waltz compositions designed especially to support these dances. Johann Strauss I wrote a waltz entitled the “Tivoli Slide Waltz” to commemorate the roller coaster–like ride, and humorously featured in his music a sliding effect a few bars before the coda. The popularity of the pleasure gardens led to such souvenirs as Tivoli hats, Tivoli watches, and even Tivoli rockets.

The Viennese Waltz continued to be popular until the 1940’s when anti-German sentiments in England, which at that time was the world’s center of ballroom dancing and related decisions, caused it to nearly be removed from the group of standard dances used in competition.

In 1950, Paul Krebs and his wife Margit, who won the Viennese Waltz in the professional German Championships, were invited to give a presentation to the world’s dance leadership in Britain. The couple danced such a beautiful Viennese Waltz that the governing body restored the status of the dance, and it remains a key part of the ballroom dance world today. Sadly, today there is another effort to redesign the Viennese Waltz, adding a vast number of new figures that make it look far too similar to every other dance, primarily because of the new judging system where couples dance competitive finals one couple at a time.